Abstrac Expressionism

Abstract expressionism is a post-World War II art movement in American painting, developed in New York in the 1940s. It was the first specifically American movement to achieve international influence and put New York City at the center of the western art world, a role formerly filled by Paris. Although the term "abstract expressionism" was first applied to American art in 1946 by the art critic Robert Coates, it had been first used in Germany in 1919 in the magazine Der Sturm, regarding German Expressionism. In the United States, Alfred Barr was the first to use this term in 1929 in relation to works by Wassily Kandinsky.

Style

Technically, an important predecessor is surrealism, with its emphasis on spontaneous, automatic or subconscious creation. The dripping paint onto a canvas laid on the by

Jackson Pollock floor is a technique that has its roots in the work of Andre Masson, Max Ernst and David Alfaro

Siqueiros. Another important early manifestation of what came to be abstract expressionism is the work of American Northwest artist Mark Tobey, especially his "white writing" canvases, which, though

generally not large in scale, anticipate the "all-over" look of Pollock's drip paintings.

The movement's name is derived from the combination of the emotional intensity and self-denial of the German Expressionists with the anti-figurative aesthetic of the European abstract schools such as

Futurism, the Bauhaus and Synthetic Cubism. Additionally, it has an image of being rebellious, anarchic, highly idiosyncratic and, some feel, nihilistic. In practice, the term is applied to any

number of artists working (mostly) in New York who had quite different styles and even to work that is neither especially abstract nor expressionist. California Abstract Expressionist Jay Meuser,

who typically painted in the non-objective style, wrote about his painting Mare Nostrum, "It is far better to capture the glorious spirit of the sea than to paint all of its tiny ripples." Pollock's

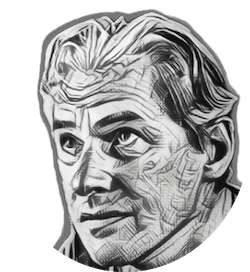

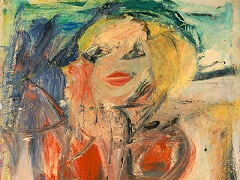

energetic "action paintings", with their "busy" feel, are different, both technically and aesthetically, from the violent and grotesque Women series of

Willem de Kooning's figurative paintings and the rectangles of color in Color Field paintings by Mark Rothko (which are not what would usually be called

expressionist and which Rothko denied were abstract). Yet all four artists are classified as abstract expressionists.

Abstract expressionism has many stylistic similarities to the Russian artists of the early 20th century such as Wassily Kandinsky. Although it is true that spontaneity or the impression of

spontaneity characterized many of the abstract expressionists works, most of these paintings involved careful planning, especially since their large size demanded it. With artists like

Paul Klee, Wassily Kandinsky, Emma Kunz, and later on Rothko, Barnett Newman, and Agnes Martin, abstract art clearly implied expression of ideas concerning the

spiritual, the unconscious and the mind.

Why this style gained mainstream acceptance in the 1950s is a matter of debate. American social realism had been the mainstream in the 1930s. It had been influenced not only by the Great Depression

but also by the muralists of Mexico such as David Alfaro Siqueiros, Diego Rivera (wife: Frida Kalo). The political

climate after World War II did not long tolerate the social protests of these painters. Abstract expressionism arose during World War II and began to be showcased during the early forties at

galleries in New York like The Art of This Century Gallery. The McCarthy era after World War II was a time of artistic censorship in the United States, but if the subject matter were totally

abstract then it would be seen as apolitical, and therefore safe. Or if the art was political, the message was largely for the insiders.

Although the abstract expressionist school spread quickly throughout the United States, the major centers of this style were New York City and the San Francisco Bay area of California.

History and Art Critics

During the period leading up to and during World War II modernist artists, writers, and poets, as well as important collectors and dealers, fled Europe and the onslaught of the Nazis for safe haven

in the United States. Many of those who didn't flee perished. Among the artists and collectors who arrived in New York during the war (some with help from Varian Fry) were Hans Namuth, Yves Tanguy,

Kay Sage, Max Ernst, Jimmy Ernst, Peggy Guggenheim, Leo Castelli, Marcel Duchamp, Andre Masson, Roberto Matta, Andre Breton, Marc Chagall, Jacques Lipchitz,

Fernand Leger and Piet Mondrian. A few artists, notably Pablo Picasso,

Henri Matisse and Pierre Bonnard remained in France and survived. The post-war period left the capitals of Europe in upheaval with an urgency to

economically and physically rebuild and to politically regroup. In Paris, formerly the center of European culture and capital of the art world, the climate for art was a disaster and New York

replaced Paris as the new center of the art world. In Europe after the war there was the continuation of Surrealism, Cubism, Dada and the works of Matisse. In the United States a new generation of

American artists began to emerge and to dominate the world stage and they were called Abstract Expressionists.

Whereas Surrealism had found inspiration in the theories of Sigmund Freud, the Abstract Expressionists looked more to the Swiss psychologist Carl Jung and

his explanations of primitive archetypes that were a part of our collective human experience. They also gravitated toward Existentialist philosophy, made popular by European intellectuals such as

Martin Heidegger and Jean-Paul Sartre.

In the 1940s there were not only few galleries (The Art of This Century, Pierre Matisse Gallery, Julien Levy Gallery and a few others) but also few critics who were willing to follow the work of the

New York Vanguard. There were also a few artists with a literary background, among them Robert Motherwell and Barnett Newman who functioned as critics as well.

While New York and the world were yet unfamiliar with the New York avant-garde by the late 1940s, most of the artists who have become household names today had their well established patron critics:

Clement Greenberg advocated Jackson Pollock and the color field painters like Clyfford Still, Mark Rothko, Barnett Newman, Adolph Gottlieb and Hans Hofmann. Harold Rosenberg seemed to prefer the

action painters like Willem de Kooning, and Franz Kline, as well as the seminal paintings of Arshile Gorky. Thomas B. Hess, the managing editor of

ARTnews, championed Willem de Kooning.

The new critics elevated their proteges by casting other artists as "followers" or ignoring those who did not serve their promotional goal.

In 1958, Mark Tobey "became the first American painter since Whistler (1895) to win top prize at the Venice Biennale.

Barnett Newman, a late member of the Uptown Group, wrote catalogue forewords and reviews, and by the late 1940s became an exhibiting artist at Betty Parsons Gallery. His first solo show was in 1948.

Soon after his first exhibition, Barnett Newman remarked in one of the Artists' Session at Studio 35: "We are in the process of making the world, to a certain extent, in our own image." Utilizing

his writing skills, Newman fought every step of the way to reinforce his newly established image as an artist and to promote his work. An example is his letter on April 9, 1955, "Letter to Sidney

Janis: - it is true that Rothko talks the fighter. He fights, however, to submit to the philistine world. My struggle against bourgeois society has involved the total rejection of it."

Strangely the person thought to have had most to do with the promotion of this style was a New York Trotskyite Clement Greenberg. As long time art critic for the Partisan Review and The Nation, he

became an early and literate proponent of abstract expressionism. The well-heeled artist Robert Motherwell joined Greenberg in promoting a style that fit the political climate and the intellectual

rebelliousness of the era.

Clement Greenberg proclaimed abstract expressionism and Jackson Pollock in particular as the epitome of aesthetic value. It supported Pollock's work on formalistic grounds as simply the best

painting of its day and the culmination of an art tradition going back via Cubism and Cezanne to Monet, in which

painting became ever 'purer' and more concentrated in what was 'essential' to it, the making of marks on a flat surface.

Jackson Pollock's works have always polarised critics. Harold Rosenberg spoke of the transformation of painting into an

existential drama in Pollock's work, in which "what was to go on the canvas was not a picture but an event". "The big moment came when it was decided to paint 'just to paint'. The gesture on the

canvas was a gesture of liberation from value - political, aesthetic, moral."

One of the most vocal critics of abstract expressionism at the time was New York Times art critic John Canaday. Meyer Schapiro, and Leo Steinberg along with Clement Greenberg and Harold Rosenberg

were important art historians of the post-war era who voiced support for abstract expressionism. During the early to mid-sixties younger art critics Michael Fried, Rosalind Krauss and Robert Hughes

added considerable insights into the critical dialectic that continues to grow around abstract expressionism.